Aid for international development is a hard sell to domestic audiences but the need for it is unlikely to go away. A significant new survey from the Angus Reid Institute and World Vision Canada sheds a light on the fundamental tension between an internationalist, value based commitment to aid and the beliefs and understanding that Canadians have about aid and development.

Those working in international development fields need to better communicate and engage Canadians on what they are doing and how it is working. Only then will a national purpose emerge to engage Canadians.

Support for international aid

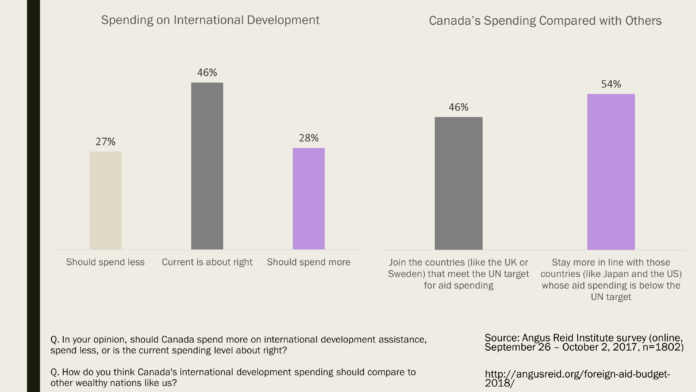

Only 27% of Canadians want us to spend less on international development assistance and an almost equal percentage 28% want us to spend more. When asked if we should aim to meet the U.N. target or stay in line with countries like Japan and the U.S. whose spending is below the U.N. target, 46% take the position we should meet the U.N. target. Optimistically, this would suggest that when people understand our commitment levels relative to others there is significant support for spending more.

The 27% who want to spend less are probably not going to be convinced to give more but there is considerable value-based commitment to aid in principle. For example, 19% strongly and 53% moderately agree (net agree, 72%) that Canada’s development aid efforts make me more proud to be Canadian. This is a solid foundation on which to build the case for a larger Canadian contribution, but that foundation needs to be energized and activated to turn support into real change.

Priorities are underdeveloped and provide little guidance

It is probably fair to say that the need for aid is large and even if Canada did more, it could not possibly address all the needs in the world. While international organizations provide information and action on a number of priorities and attempt to provide leadership for the world, at the national level the lack of a national purpose means international aid becomes a weakly constrained influence on the political agenda. This translates into well meaning, value-based attitudes that do not translate into more assistance. There is no question that Canadians do not view the issue of aid purposely. By that I mean, that there sense of what we should be doing is not closely connected with how they see the problem.

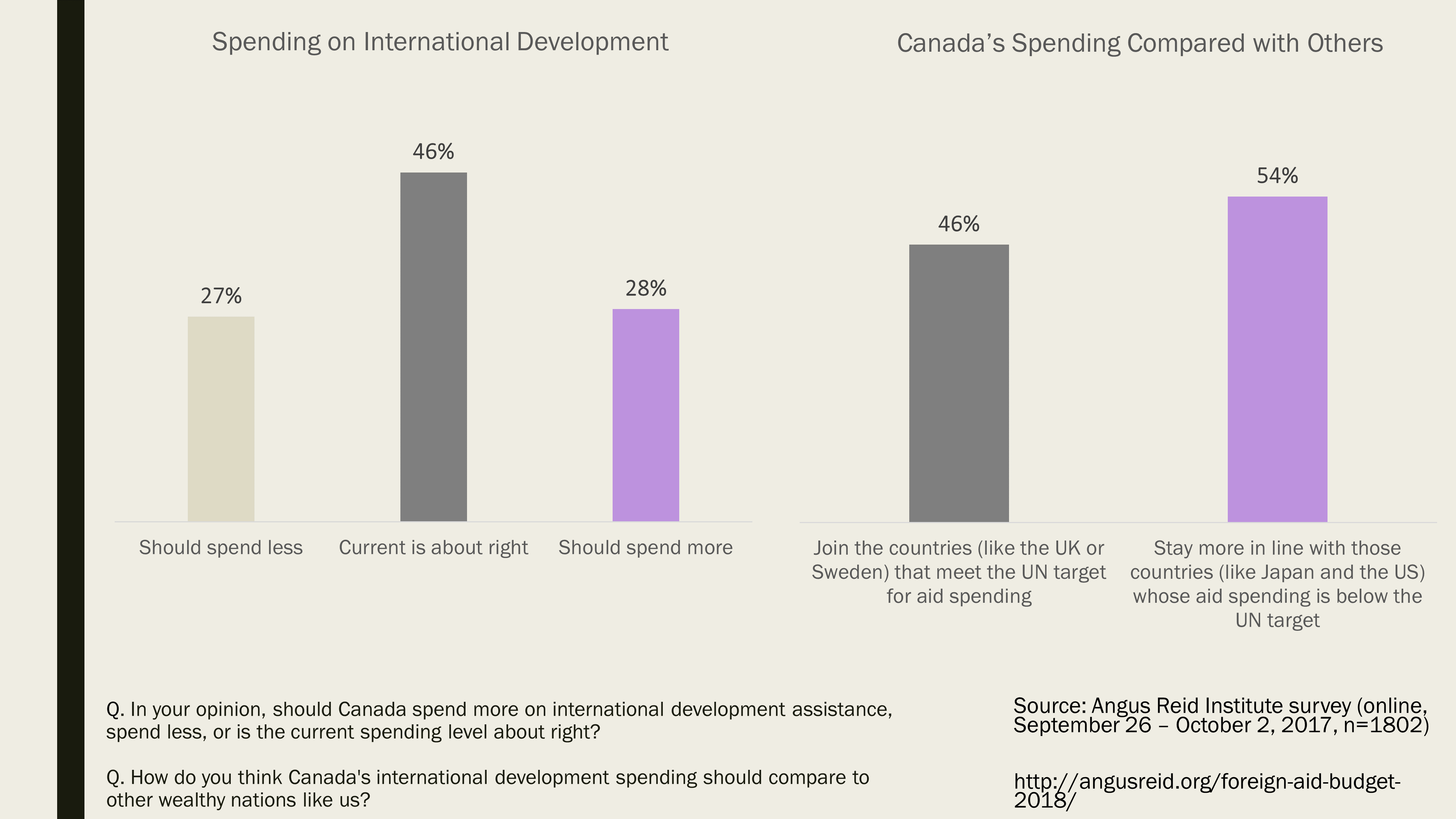

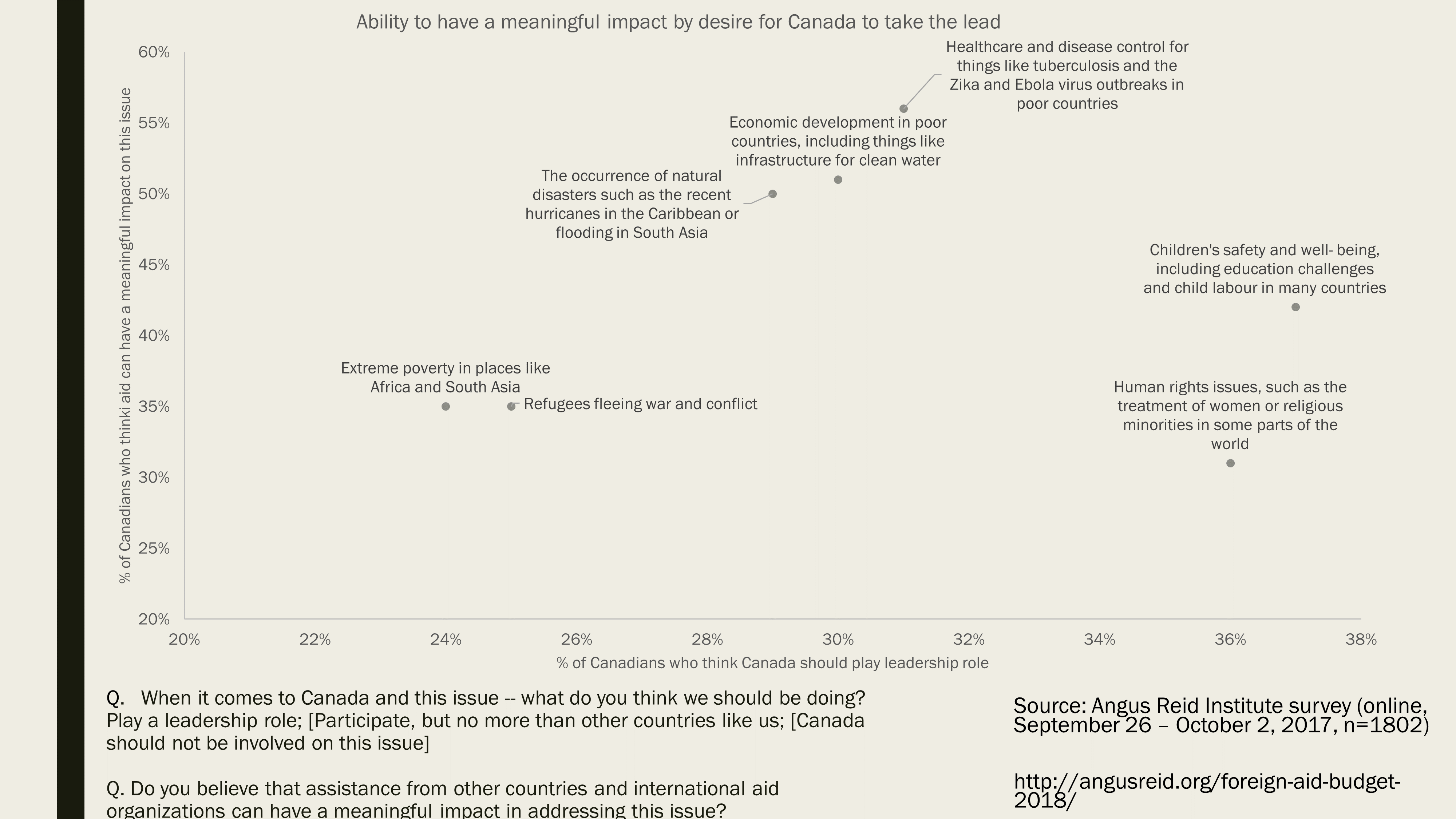

The Angus Reid Institute survey asked about 7 international development priorities along a number of dimensions, including the nature of the problem, public concern, the ability of aid to make a meaningful difference and the role Canada should play. A particularly useful way to understand how Canadians think about these issues is to map them on a grid of two dimensions. Below we compare perceptions of the problem (% who think it is getting worse; horizontal dimension) with the extent to which aid can have a meaningful impact (vertical dimension).

- The two areas that Canadians are most likely to view as getting worse are the occurrence of natural disasters and refugees fleeing war and conflict. But there is a big difference in the perceived impact of aid on these two issues. Aid is viewed as more impactful in dealing with natural disasters compared with refugees.

- The two other issues Canadians think aid can be impactful are healthcare and disease control and economic development in poor countries. These are not areas that Canadians are as likely to think things are getting poorer.

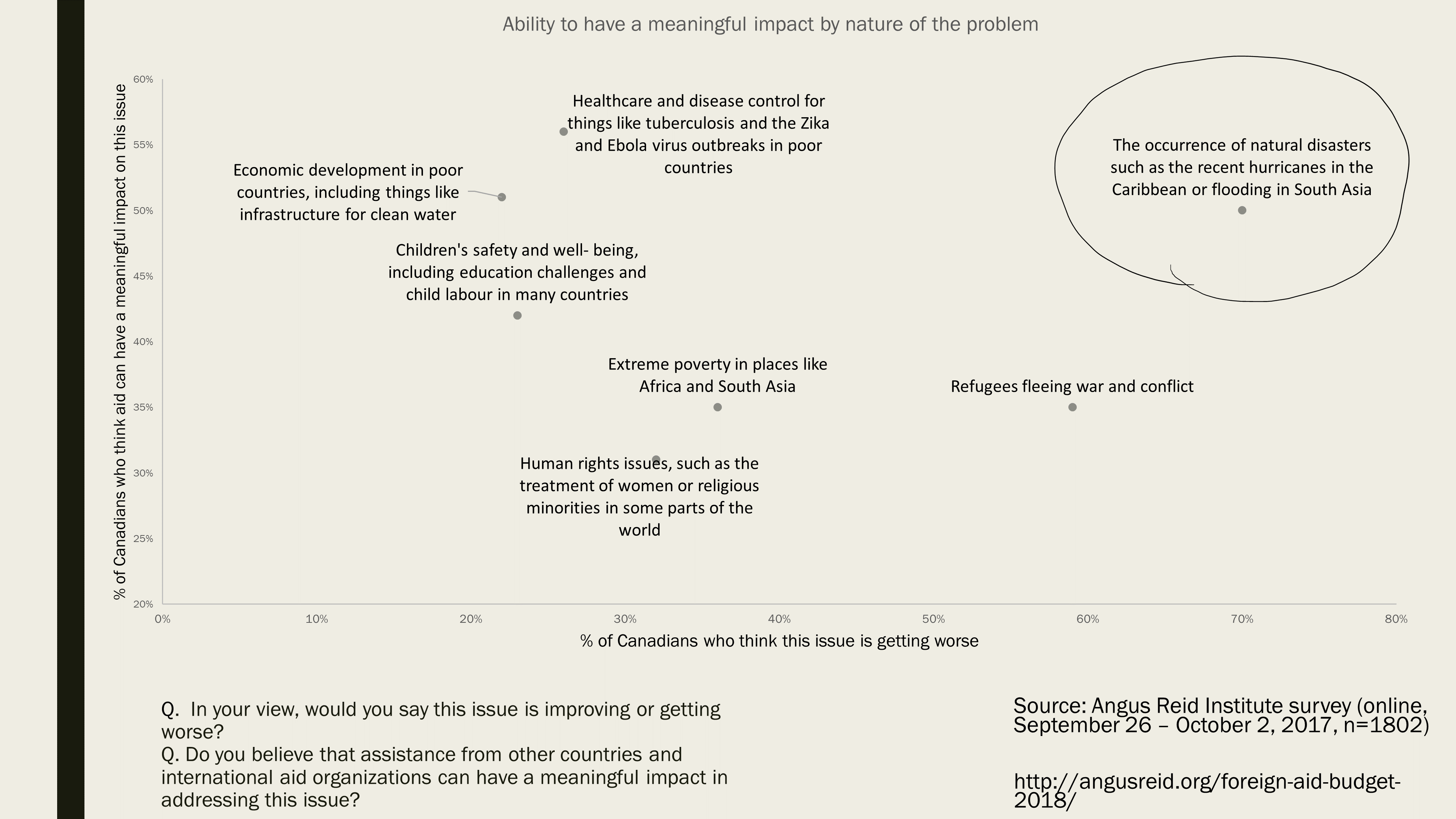

Many of the issues Canadians think can be most impactful are not ones that we view as getting worse, which is interesting because if the problem is getting worse the implication is that we need to do something. But the areas Canadians most want us to be active/ take a leadership role are neither the issues that are getting worse or the ones that aid can be most effective at. Consider (below) that the two areas Canadians most want Canada to play a leadership role (right side of the grid) are children’s safety and human rights issues. Effectively these are the issues that most align with values.

Implications

Canada will always be called on in the event of an emergency to help but how we help and how we structure our aid is all about priorities. An ideal priority has three things. First, it is one that aligns with values. Second, it is something that we have the tools to be effective at. Third, it is in real need for change. Public priorities as measured here provide us with conflicting advice about how Canada should focus and develop its international development assistance.

Based on values, the focus on human rights and children’s issues will be out of touch with being effective with aid. The focus on what is getting worse leaves us with assisting with refugees or with disaster relief that are not as high priorities from a value perspective.

The closest narrative that speaks to Canadians is one around the response to natural disasters. From the public perspective, the problem is getting worse and aid is very effective. These stories always speak to people because of the fact that there is a “no fault” aspect of a disaster. The suffering is also thrust upon us. It could serve as part of a national purpose except that it is not an area Canadians want us to be leaders in.

Whether the goal is to convince the government or to convince individuals to contribute more, it will be more likely to be reached if it resonates with public priorities and values. This leaves an important task — communicate effectively to energize a national purpose for aid which probably require either:

- to find ways to convince Canadians that aid for children’s safety and human rights issues is effective, or

- to find ways to convince Canadians that issues such as healthcare and economic development are urgent and/or more rooted in Canadian values (so that Canadians believe we should take a leadership role).

Convince may not be as much about changing minds as it is about changing the narrative. Doing one of these things will better align priorities and help address concerns about the effectiveness of aid, the trust in international aid organizations, and the hopelessness of the need.

Sources: Angus Reid Institute survey conducted with World Vision Canada online between September 26 and October 2, 2017 (n=1802). More information here and here.